From volume 72, spring 2005

By Thomas Exner

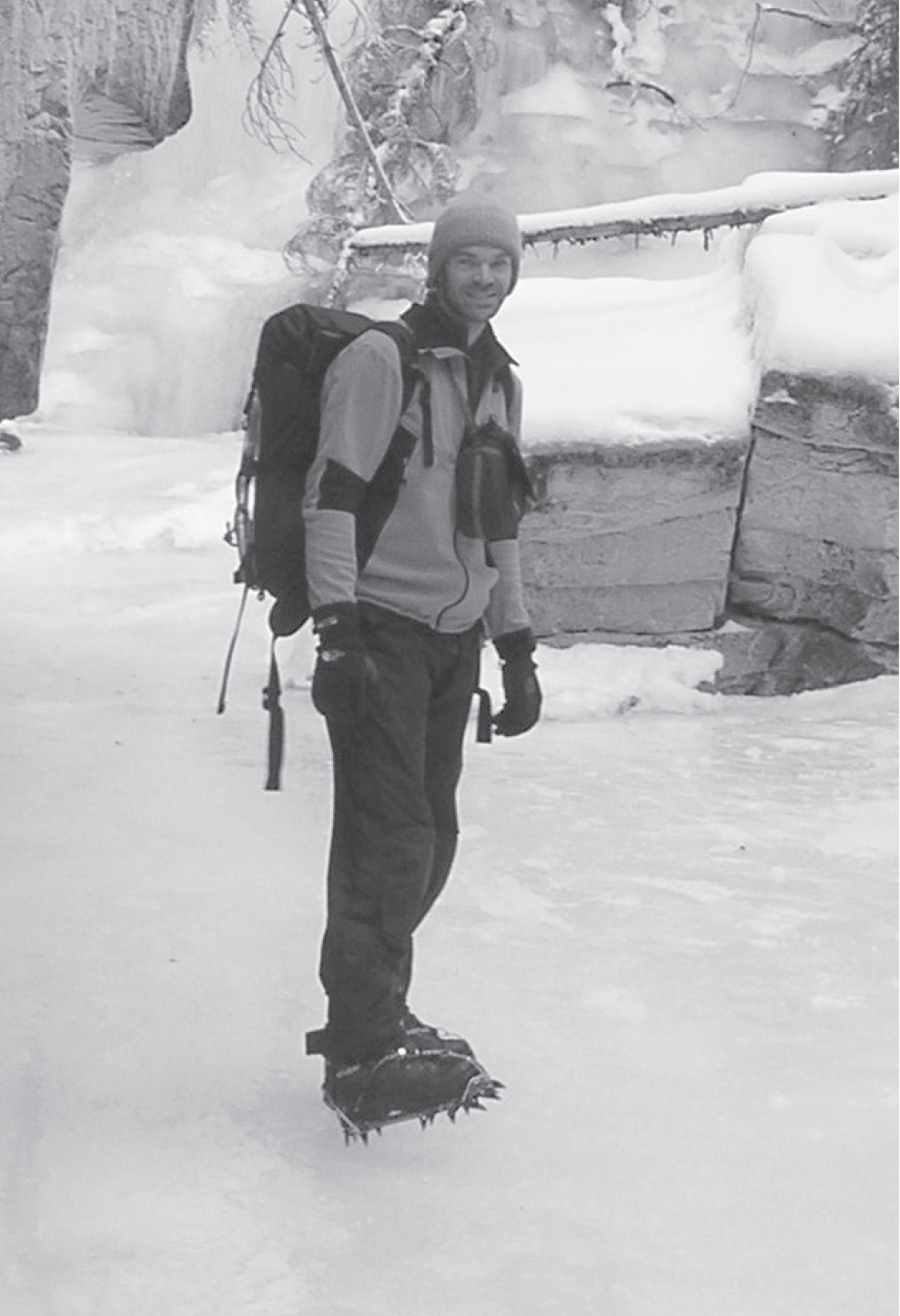

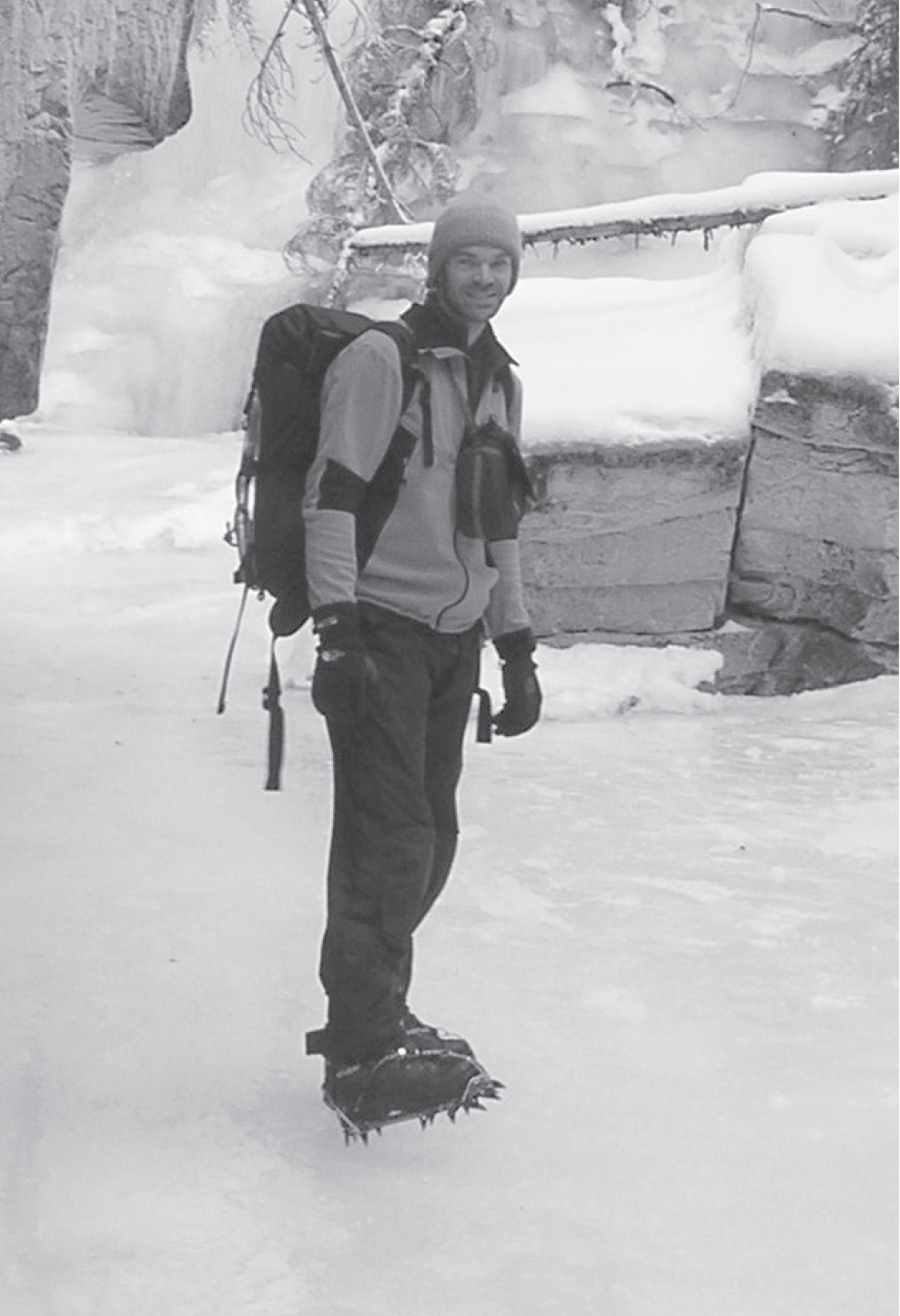

At around 5:30 in the morning my girlfriend Jacqui and I drank our morning tea while gathering our tools and crampons in preparation for our last climb of the season. I was visiting her in Canada for the second time that season and had already spent a few weeks in the Banff area prior to that day. Our objective was Professor Falls. A nice classic, mellow ice route with a great reputation, it would be the first time climbing it for both of us.

Every time we ventured out in the mountains we put a considerable amount of effort into planning. Most of the time we would gather all the information available to us, such as checking out the avalanche bulletin, analysing weather maps and talking to the public safety wardens. This was the only day we didn’t do our usual homework. We were familiar with the local conditions and comfortable with our decision relying on the information we had. We didn’t know that by not calling the safety warden we were missing crucial information. That decision almost cost us our lives.

That morning we rode our bikes along the long approach until we could not take them any further. Professor Falls is located on the north side of Mt Rundle, a popular climb with close proximity to Banff. As we rode along on that chilly morning, I remember discussing the weather and the frost on the ground. This was a good sign for that early March morning. We expected to finish the climb before noon when temperatures were going to get too high. Winter was starting to feel a little warmer by that time and signs of overnight freezing were encouraging to us. We wanted to climb the route a few days earlier, but a snowfall forced us to postpone our plans. It was now about four days since this last snowfall and we were the first party to start the climb that day.

Walking up the last metres to the climb we saw the first pitches in really impressive conditions. We were totally excited about the climb and the opportunity to spend our last day in the Rockies on such a nice piece of ice. Viewing the surrounding terrain from this point of view there is no obvious avalanche danger, although we knew the potentially dangerous slopes were way above. It looks more like a wonderful climb in impressive surroundings with minimum objective dangers. Everything seemed to be perfect.

Professor’s is popular for a good reason. The approach leads along the Bow River, offering impressive views of the huge north face of Mt. Rundle and an area known as Trophy Wall, where some of Canada’s hardest and most famous ice climbs can be found. Professor’s itself consists of several steps of steep and fat ice, separated by flat bands and gullies. The first pitch, just a short walk off the Bow Valley trail, offers moderately steep and excellent ice squeezed in between two rock faces. The flat bands on top of each step provide comfortable belaying and offer good views above the Bow Valley.

When we started the climb we were just ahead of another party. It took us a while to get going on the the first pitch, but after warming up and getting a feeling for the ice everything ran smooth and we enjoyed the excellent ice pitch after pitch. At one point, somewhere near the middle of the climb, we met a solo climber heading down who seemed to appear out of nowhere. As Jacqui arrived at the anchors after seconding the pitch before the last crux pitch, she continued ahead on the final horizontal ice section. Walking a rope length ahead of me, she and I moved together as we approached the final pitch. My eyes were focused on the crux pitch, anticipating these last metres of perfect ice. I was coiling up a few slings of the rope since I was walking a bit faster than Jacqui. Time-wise, we were doing pretty well since it was still well before noon. We were about to finish the climb soon, rappel down, and still have enough time to enjoy the afternoon.

Suddenly I heard a bang above me, forcing me to look way up over the huge rocky cliff several hundred metres above us. What I saw was shocking – a huge powder cloud. At first I thought it was too far to the right to reach us and tried to relax. Keeping my eyes on the cloud for a couple of seconds, I realized I was wrong. It was growing incredibly fast and I knew for sure – a huge avalanche will come right down over us.

I yelled to Jacqui who hadn’t yet noticed anything. “Avalanche, go to the right!” She turned around to me with a frightened expression on her face. She couldn’t see what was going on from her perspective and yelled with a fearful voice, “What should I do?” I told her again to go to the right and hold on.

Since the powder cloud was coming from the right, I hoped the little rocky cliff on the right hand side of the gully would provide shelter. I was positioned near the edge of the gully and jumped to the right under some slightly overhanging rock, getting out of sight from Jacqui and possibly seeing her for the last time. I tried to get into a comfortable position while trying to build some air space with my hands and arms in front of my head. Then I noticed a small tree just to the left of me. I ran around it once, wrapping the rope around its trunk. This would be the our only anchor.

I was sitting back pressed against the cliff and waiting – for the end? I remained surprisingly calm. I don’t know why, because we would probably die. I can’t tell how much time passed since I heard the bang. Maybe it was 10 seconds or maybe 30, I don’t know. It seemed like an eternity. We did have enough time to communicate, position ourselves, run around a tree, reposition, and even wait.

At that moment I expected a huge shock wave which would probably kill us before the solid snow hit. I could see the enormous powder cloud quickly approaching the gully, gaining size and strength as it got closer. It was getting dark all around, stormy and loud like a huge snow storm with extreme winds. There was a heavy rumbling sound. I couldn’t see what was going on.

There was no shock wave, we are lucky. But most likely the flowing snow would cover us with metres of debris. Then it became silent and light again. I couldn’t feel any snow burying me, I was just covered with a thick layer of blown snow. I looked back down the gully. There was still snow flowing down into the main gully, totally blocking it. Most of the snow was funneled around us and managed to pile in the gullies behind us.

There must have been more than six metres of snow piled up just a few metres behind me. I waited a few more seconds until nothing was moving. I stepped forward, yelling for Jacqui. She was last located closer to the middle of the gully and I was scared, knowing her position and the massive amount of snow that just used our climbing route as a funnel. Then I heard her voice. She was a bit freaked out but fine, thank God. She told me later she had bruises on her knees and legs from clinging so hard to that little rock cliff.

We thought of leaving the gully to the side as quick as possible, fearing more avalanches to come. But there was still the other party below us and the solo climber. All three people would be not too far below us and we were suddenly overwhelmed with additional fears that they didn’t make it. We turned our transceivers to search and went down the gully as quickly as possible. Jacqui used her cell phone to contact the Park Wardens, informing them about the avalanche and the possibility of three climbers caught.

The gully was totally changed. The middle part, where we were walking just minutes before, was deeply filled with avalanche debris. The smaller steps we had climbed were practically gone and one shorter pitch had totally vanished in the debris. We were able to slide down much of the gully before we came to some anchors to rappel the rest of the climb. Surprisingly, we saw the other party doing well and on their way up to look for us. They had kept a steady pace behind us for most of the climb, but luckily managed to lose some speed and just missed the many tons of heavy snow that might have killed them. The solo climber had passed them on his way down and was well out of danger.

We called the wardens again to report no one was caught but the helicopter was already on the way – almost Euro style. Later, the warden told us they were planning to sling us out since there was still snow in the start zone. The fracture line was about 150 m wide and averaged a half-metre in depth. The avalanche fell about 700-800 m, then hit flatter terrain where it probably lost much of its energy before it reached us. The debris piled up everywhere around us except the side of the gully where Jacqui and I were hiding. It was incredible, and eerie, to look around and see the snow piled in every direction except for the two places where we stood.

We decided to rappel down together with the other party and finish this adventure quickly. At the top of the final pitch we met an American party on the way up, regardless of the powder cloud that had even reached the base of the climb where they had been standing. We really had to convince them not to continue, despite the obvious clues of avalanche danger. It was already noon at this point and so warm that it was slightly raining.

On our way back to the car we could see the top of Mt. Rundle covered in clouds with strong winds. We observed a small slide on the steep cliff to the right of the climb. As we got back to Banff the skies were clearing a bit and the sun came out. It was really nice and warm just like nothing happened. In the safe shelter of a pub we reflected upon the past few hours and a mix of emotions came up in me. I was just too calm up there in the gully. I slowly started to realize what happened to us that morning and what a huge gift it was that we were still alive. All our guardian angels had a pretty busy day.

So what went wrong that day? Is it just a freak thing that happens, an acceptable part of being in the mountains? “Yes’’ would be a really discouraging answer. It would be difficult for me to avoid all climbs with possible avalanche risk above. This cannot be the answer. We tried to figure out what went wrong in our decision-making process that day.

We postponed the climb due to a snowfall with significant winds. On the evening before our last day in Banff we discussed the situation again. The daytime temperatures had been relatively mild but still below freezing overnight in the alpine, promoting a settling of the storm snow. Everything that hadn’t avalanched already should not be triggered naturally. The hazard was rated considerable, focusing on sun-exposed slopes that might become dangerous due to daytime warming. We didn’t expect any natural activity on north-facing slopes. To be on the safe side, we decided to start at the break of day to get off the climb before noon. Based on this information we decided it was safe to go for this climb.

We didn’t know about the warmer temperatures at higher elevations, which might have been one reason for the release of such a big natural avalanche. The little storm just around Mt. Rundle put more drifting snow on the slopes above the climb, enough to trigger it. This new wind loading and the temperature inversion were hard to foresee, neither of which were forecasted. But the crucial information we missed was that natural avalanches occurred on all aspects the day before we went on the climb. This knowledge would have been a clear indicator not to climb Professor Falls that day and was easily available by a simple check with the Wardens. It was our mistake to not utilize all the information available to us.

The other factor in our mistake is less obvious. It was our last day in the area and we wanted to spend it on a nice, popular climb that neither of us had done. Looking back, I am pretty convinced that subconsciously this influenced our decision. We possibly would have made a different decision if there wasn’t the subtle pressure to end our season with a classic climb of the Rockies.

In avalanche country, most of the time you have no way of knowing if your judgement matches the real conditions. You never know how close you are because most of the time there is no feedback. It’s the feedback, though, that can sometimes be fatal. Going too long without any feedback might suggest that you always make the right decision. Looking back on the lesson from the Professor,

I am happy that I experienced it. It brought me back to the ground. I might have been out in the mountains too long without any feedback. I am sure it could have been avoided and it wasn’t just Mother Nature playing tricks on us. There were mistakes in our decision making progress. This sounds promising to me, because it can be improved. Jacqui asked me once how I know whether it’s safe or not. I told her you never really know. It’s sometimes just a gut feeling. She was not amused by my non-scientific answer and responded with, “Great. Thanks,” and kept skiing.

The night before the climb that was so close to being our last, she suffered from great discomfort while sleeping and woke up with a troubled and unsettled feeling. At least we both know now what I was trying to say.