From volume 91, winter 2009-10

By Manuel Genswein

1.INTRODUCTION

A variation of companion rescue is performed by clients of commercial guiding, off-piste and helicopter skiing organizations. The experience level of non-commercial back-country users is typically similar and their training level has primarily been achieved by their own motivation and sense of responsibility. Hence during an accident the level of competence amongst buried and non buried subjects is similar. In contrast, the level of responsibility, preparedness and training between clients and guides in commercial operations are hugely different.

By emphasizing “Safety,” some commercial operators create expectations that are difficult to fulfil in the context of ski touring, heliskiing or off-piste skiing. This does not help the clients’ mental preparedness for an accident. The motivation to train their clients is partly due to their own interest and partly due to laws concerning product liability. In countries with harsher product liability laws the training of clients is implemented more thorough than in countries where those laws barely exist. Another interesting fact is the diverging opinion among guides as to the usefulness of training their clients.

Some guides highly value a good base education also for their own good in order to be rescued. Others just hang an avalanche transceiver around the neck of their clients and have resigned themselves to never having a hope of being rescued by them. Because of the hopeless attitude of the latter group, typically their clients don’t get equipped with probe and shovel, which makes a rescue basically impossible. The combination of probe, shovel and transceiver—called “personal rescue equipment”—forms the base of an efficient rescue. This holds true even for commercial backcountry operators. In this context, the potentially rapid availability of rescue equipment—e.g. Helicopter aided companion rescue by heliski companies—is not enough of an excuse to fail in outfitting each client with their individual personal rescue equipment.

The topic of training and equipping clients appears especially important, if one considers that statistically it is the first person to enter a slope, that has clearly a higher probability to release an avalanche than subsequent persons.

2. HOW MUCH TRAINING IS REALISTIC AND ADEQUATE

Central to this discussion is the amount of time needed to adequately train the clients. The threshold for clients and guides is rather low compared to non-commercial groups, where education is a substantial part of the work for a guide.

After extensive enquiries with many commercial guiding, off-piste and helicopter skiing organizations (daily and weekly operators) in regards to an “acceptable” amount of time allocated for client training, the choice for an adequate and practicably possible time frame was 15 minutes. For those operators who have always valued fundamental training, this may appear quite short. For those guides that have “just hung the transceiver around the clients’ neck,” each minute appears to be too much. Ultimately the 15 minute time frame meets the requirement for “acceptance” and “usefulness.” Especially those who see the situation in a rather pessimistic light might put a little more importance into adequate training and personal rescue equipment for clients once they see the rather convincing test results.

Increasing client training time from 15 to 30 minutes would with great likelihood not significantly increase rescue efficiency. In the additional time no great advantages in search and rescue techniques are achieved. A valuable addition would be a short practice of a rescue scenario. Within the chosen time frame it is possible to learn search/ strategy for multiple burials by applying the “marking” feature.

The goal of this project and the field test is to design a training module for client training. After extensive enquiries with many commercial guiding, off-piste and helicopter skiing organizations (daily and weekly operators), the choice for an adequate and practicably possible time frame was 15 minutes. Immediately after the 15 minute training, the clients were asked to search for and excavate two buried subjects in a 50m x 80 m field. Based on the quantitative results of this test, conclusions as to the efficiency of the training module were made and the subsequent module was changed to optimize the content for the next group.

3. TEST PARTICIPANTS

All participants were clients of guides and ski instructors. For the field test the clients were separated from their guides. 83 clients participated in 14 groups. The clients‘ knowledge was varied; most were beginners. The average age was 53; 17 clients were older than 65. Guides were instructed not to hold any special lessons prior to the test. At the time of the test clients knew each other for a couple of hours up to a couple of days.

4. TEST ENVIRONMENT

4.1 Test fields

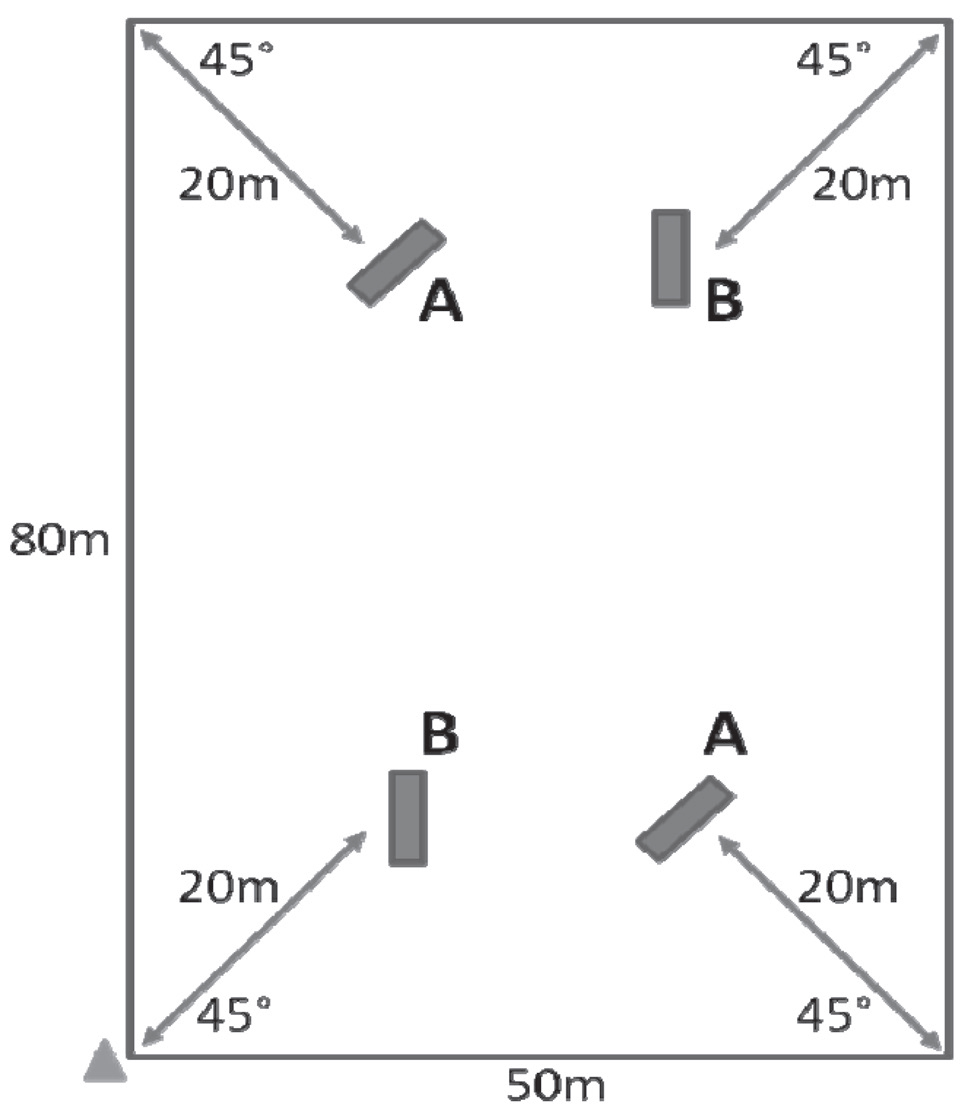

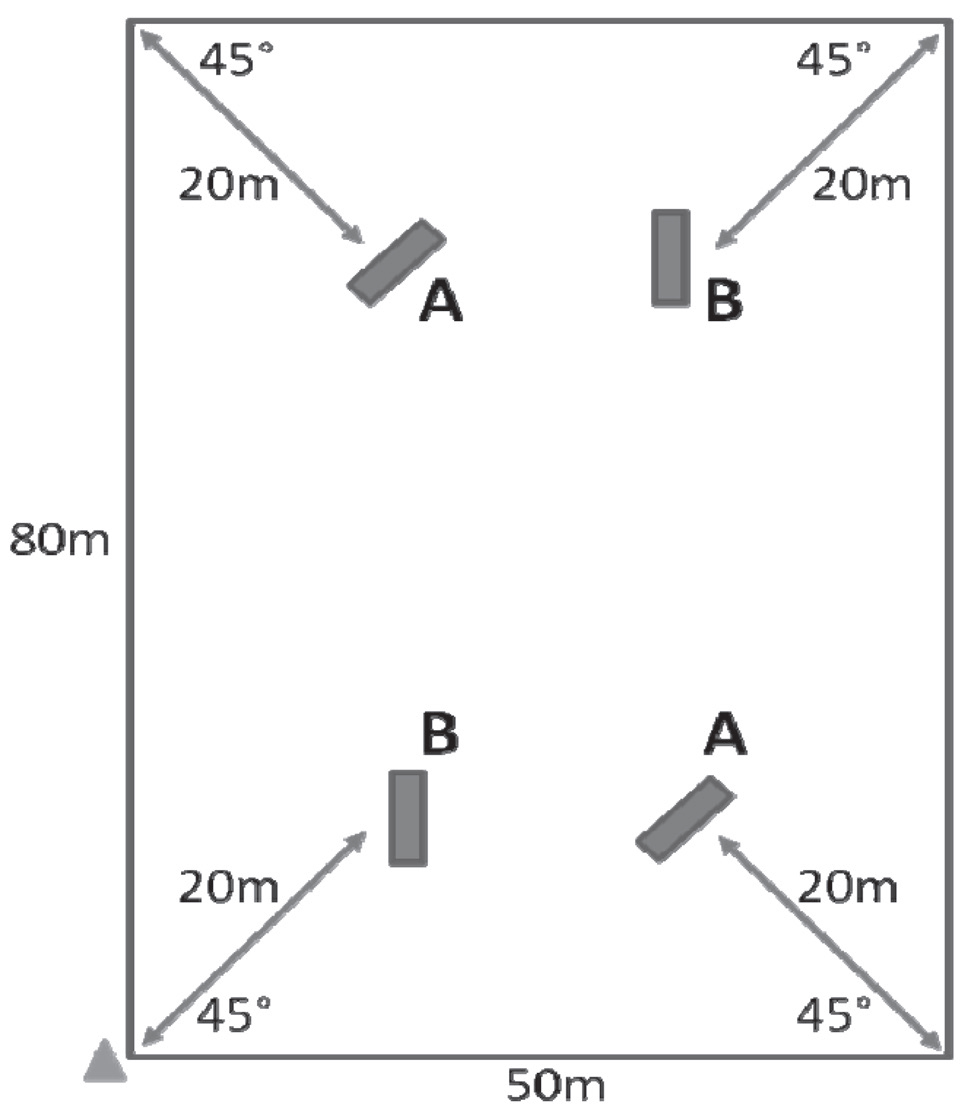

For efficient data recording, two test fields were used. They were 50m x 80m (see illustration 1), which represents the median size of “survived recreational avalanches” in Switzerland. Slope inclination was approximately 5 degrees in the lower third and up to 20 degrees in the upper end of the field.

Starting point for all rescuers was always a corner at the bottom end of the field (see illustration 1, triangle). In comparison with a typical off-piste avalanche accident this constitutes a significantly more difficult scenario. During an off-piste accident significantly more than 50 % of all rescues are conducted from the top. Foot penetration was between knee and hip deep. This cost the rescuers a significant amount of time and effort, as they were only allowed to move without skis.

Illustration 1

4.2 Buried Subjects

The “victims” were two bags normally used to carry firewood, sewn together and filled with straw. The approximate size per “victim” was 180cm x 70cm. When burying the victims, the snow was stomped down layer by layer. Burial depth was 50 cm – 100 cm, representing the average burial depth in off-piste avalanche accidents. The buried subjects were equipped with remote control avalanche transceivers with probe detection device. Two buried subjects were activated per search, combination A-A or B-B.

5. TEST PROCEDURE AND DATA RECORDING

All groups were lead to the site by their respective guides. Skis and other non-rescue specific gear was left behind. Guests received adequate probes and shovels. Only three-antenna avalanche transceivers with specific “marking” function to eliminate a previously located signal were used in this test. After the group arrived at the site they received a 15-minute instruction. After the short instruction participants were presented with the rescue scenario.

Details recorded:

● Signal search time: The time until the first signal is received.

● Coarse search time: The time from the first point of reception until the signal decreases for the first time as the rescuer walks over the buried subject.

● Fine search time: The time when a clear minimum of distance (or maximum of volume) can be isolated.

● Pinpoint search time: The time when the rescuer hits the buried subject with a probe.

● First visual contact with the buried subject

● Full body free

6. PRACTICAL TRAINING MODULE

The 15-minute training module included the following content:

● General goal and overview

Search procedure including “airport approach”

Mounting of the probe and shovel

● Basic handling of transceiver

“OFF – SEND – SEARCH.”. Switch SEND fg SEARCH two or three times on command, all together, repeat until a routine has been established. Verify after each step, if all participants were able to switched to the appropriate mode.

● Practical search with explanation of each search phase.

Practical search of one buried subject at 35 m distance. Transceiver angled at 45 degrees to group g curved search path, which forces attention on direction indication on transceiver. Flux lines / flux line characteristics not discussed. Clients follow with their transceiver on receive. Group is halted before next search phase to explain the next steps.

● Signal search

If distance to buried subject is greater than range of transceiver g signal search, as per diagram on back of transceiver, is necessary. 3D rotation until signal is detected. Move – no life has yet been saved by just standing still!

● Coarse search

Hold device horizontally “move in direction of arrow.” Does distance indication decrease or increase? At distance 10: airport in sight g slow down!

● Fine search

Approach g slowly and precisely, holding transceiver close to snow surface. Absolutely no grid search! Place shovel at the point of smallest distance indication.

● Pinpoint search with spiral probing (4) up until the “hit” at approximately 1.5 m burial depth. Leave probe in snow. “Mark” with marking function on transceiver; wait until all clients have marked. Activate second transceiver in 15m distance. All guest will locate the second transceiver on their own.

● Excavation

Short explanation of V-shaped snow conveyor. Put clients in V formation while teaching basic concept—“cut blocks” and central snow conveyor belt, paddling motion and correct handling of the avalanche shovel. Actively running of conveyor belt. Explanations and corrections while the clients work. Let conveyor belt run for 3 – 4 min. Practice rotation on command, no specific instructions as to behaviour when first contact with buried subject.

7. RESULTS

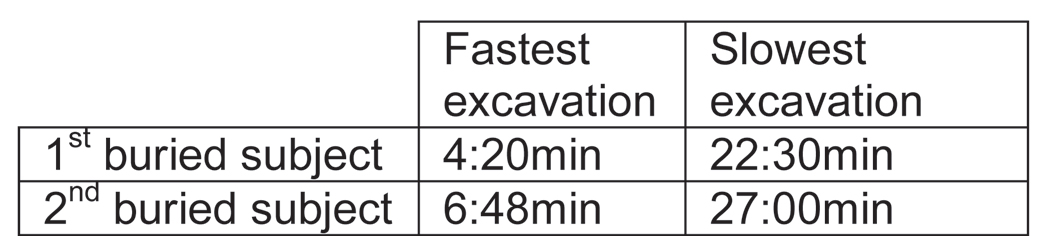

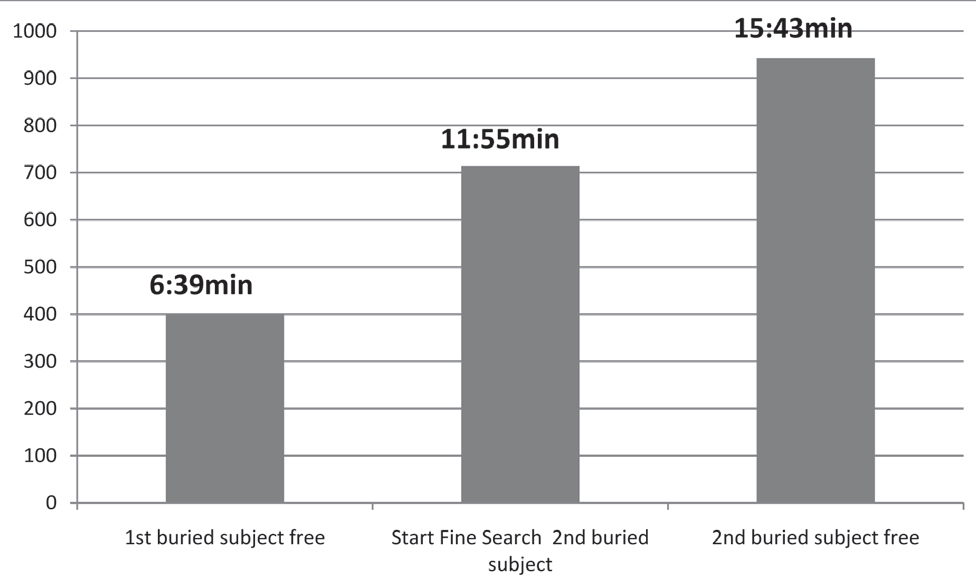

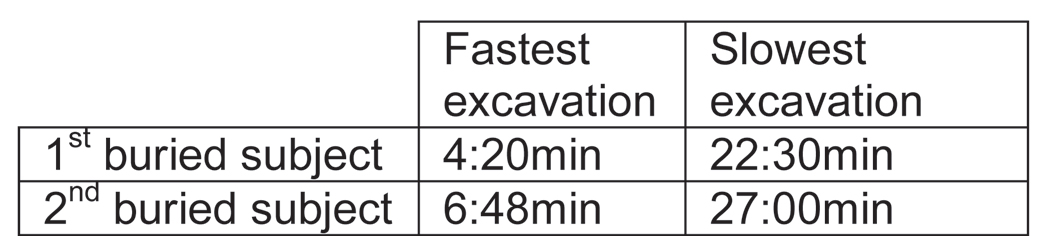

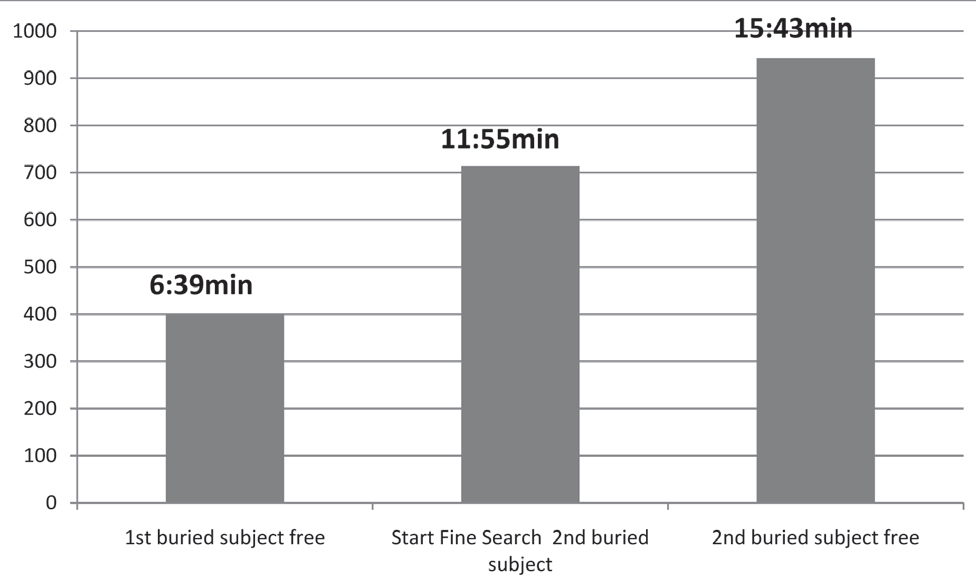

14 groups of 83 clients reached the following median times for locating and completely excavating the buried subjects. Fastest and slowest times were measured as follows: The biggest time lag resulted between the completed excavation of the first buried subject and the start of the fine search for the second buried subject. Those rescuers who did not locate and mark the first buried subject themselves confessed often great difficulty in physically removing themselves from the first buried subject and moving towards the second buried subject, as the distance indication on their transceiver increased.

8. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The field test results prove that very realistic survival chances exist within a commercially guided group if the guide is buried. The surprisingly short search times make it clear that short and efficient guest training makes sense. The common opinion that a guest cannot ensure the survival of the guide is hereby not accurate and has clearly been proven wrong.

Despite the short training time, the second buried subject was located and excavated in all scenarios. Clearly this result can be attributed to the technically advanced transceivers with marking function. Problems arose for the rescuers who did not mark the first buried subject while transitioning to locate the second buried subject. Those problems indicate that transceivers could further be improved. A basic requirement to achieve the above results is to always outfit clients with modern rescue equipment—probe, shovel and transceiver with “marking” function. The author recommends that instructors use the guidelines and techniques outlined in this paper when training their clients.

The full paper may be downloaded at www.genswein.com