An Atmospheric River Event in the Colorado Rockies

From Vol. 119, winter 2018-19

By Brian Lazar

THE ASPEN COMMUNITY was rocked April 8, 2018. A long-time and beloved member of the local search and rescue group was killed in an avalanche while skiing recreationally in backcountry terrain adjacent to Aspen Highlands ski area. The entire episode was witnessed by members of the Aspen Highlands Ski Patrol (AHSP) from the ridge and summit patrol shack. It was also captured by a ski area web cam.

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) issued a special product called an Avalanche Warning the morning of the accident. Both the victim and his partner were very experienced backcountry travelers. Both knew the terrain intimately. They witnessed and crossed fresh avalanche debris on adjacent slopes to reach their objective and the site of the accident. The compelling nature of the clues had the snow safety community asking: What happened?

After a summer to reflect on this accident, it’s clear there were several contributing factors and some key take-home lessons that reinforce classic risk management advice in avalanche terrain. Yet it’s hard to escape one critical factor: The two people decided to enter complex avalanche terrain at the tail end of an unusually warm and wet storm.

THE STORM

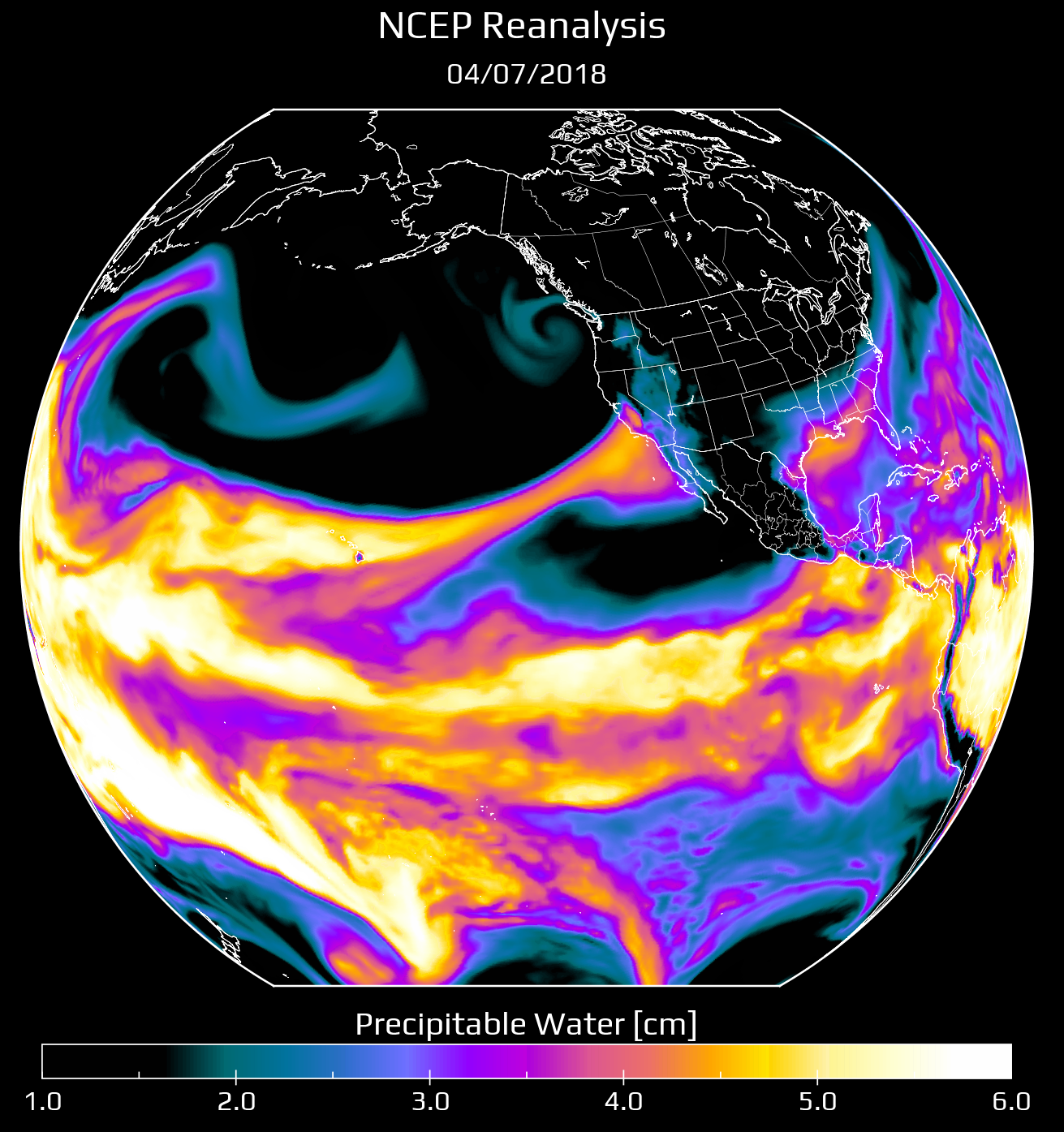

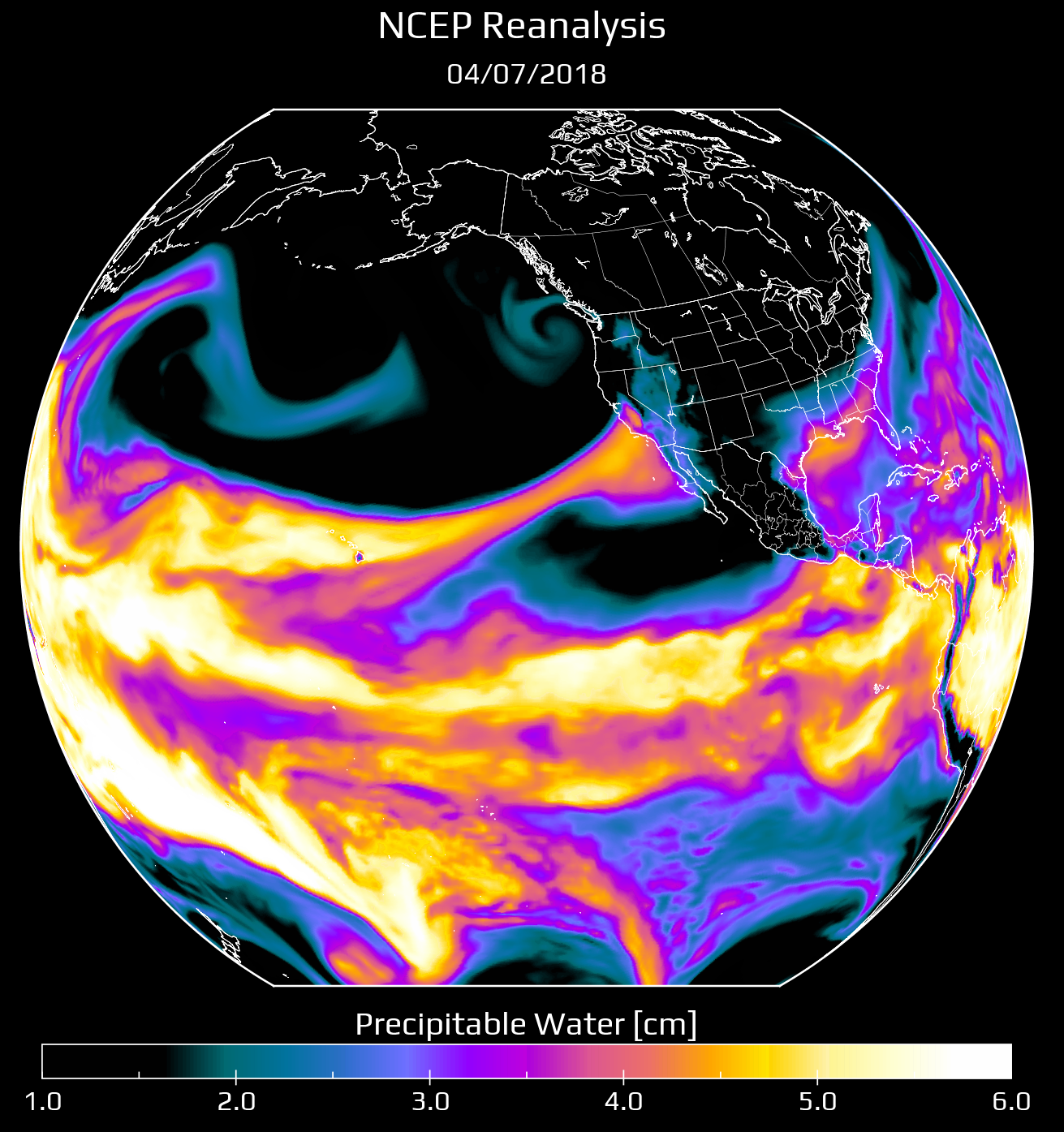

FIG. 1: NATIONAL CENTERS FOR ENVIRONMENT PREDICTION (NCEP) OF PRECIPITABLE WATER ON APRIL 7, THE DAY PRIOR TO ACCIDENT. THIS SHOWS THE ATMOSPHERIC RIVER OF DEEP PACIFIC MOISTURE HEADING TOWARDS COLORADO(IMAGE COURTESY OF NICK BARLOW)

From April 1 to April 5, conditions were typical of early spring weather in Colorado. There were several centimetres of new snow, and above freezing daytime temperatures with below freezing nighttime temperatures. From April 6 to 8, an atmospheric river funneled deep Pacific moisture into the region (Figure 1). The sounding on April 8 from the National Weather Service in Grand Junction (approximately 150 km west of Aspen) showed the atmosphere had deep moisture to around 300 mb, and precipitable water was over 250% of average for the date. Some portions of the state picked up over 150mm HSTW in the 3-day period.

In the Aspen area, the storm began with above freezing temperatures to around 3600 m, and rain as high as 3400 m. Temperatures cooled as the storm progressed, and snow levels dropped. From April 6 to 7, AHSP measured less than 8cm of dense snow (HN24). On the morning of the accident, April 8, AHSP measured HN24 20cm (38mm). Another 3.8cm of snow fell later that same morning. HST totals were 31cm (43mm).

This was an unusual storm for Colorado, even for spring conditions. It was warmer and wetter than what most avalanche professionals in the area typically encounter. Rain at high elevations at the front end of a storm was rare, as was the high-density new snow that followed. The storm loaded a snowpack typical of the region: thin, cold, and with pronounced persistent weak layers.

FIG. 2: THE ASHP SNOW SAFETY TEAM WAS ALSO CONCERNED ABOUT THEIR IN-BOUNDS TERRAIN. HIGHLAND BOWL, ON THE OPPOSITE SIDE OF THE RIDGE FROM THE ACCIDENT SITE, REMAINED CLOSED ON THE DAY OF THE ACCIDENT.

THE EVENT

The storm cycle had many avalanche professionals on edge. At the CAIC we engaged in discussions both inside and outside our group about the widespread uncertainty. How would the snowpack respond to the rain, storm snow density changes, and rapid HST settlement?

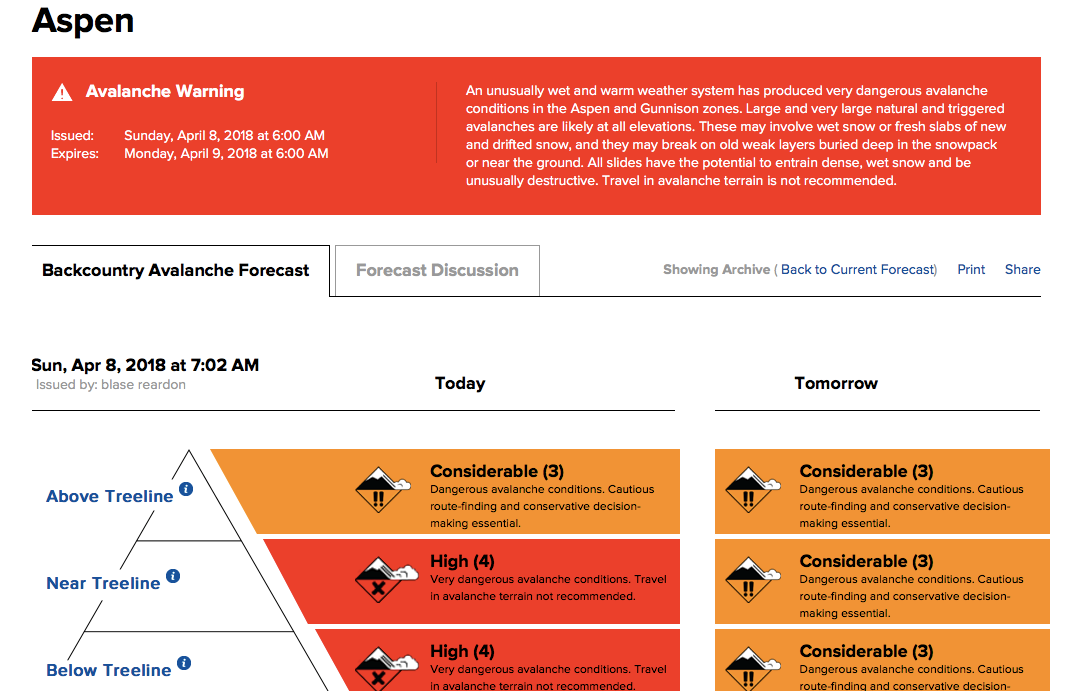

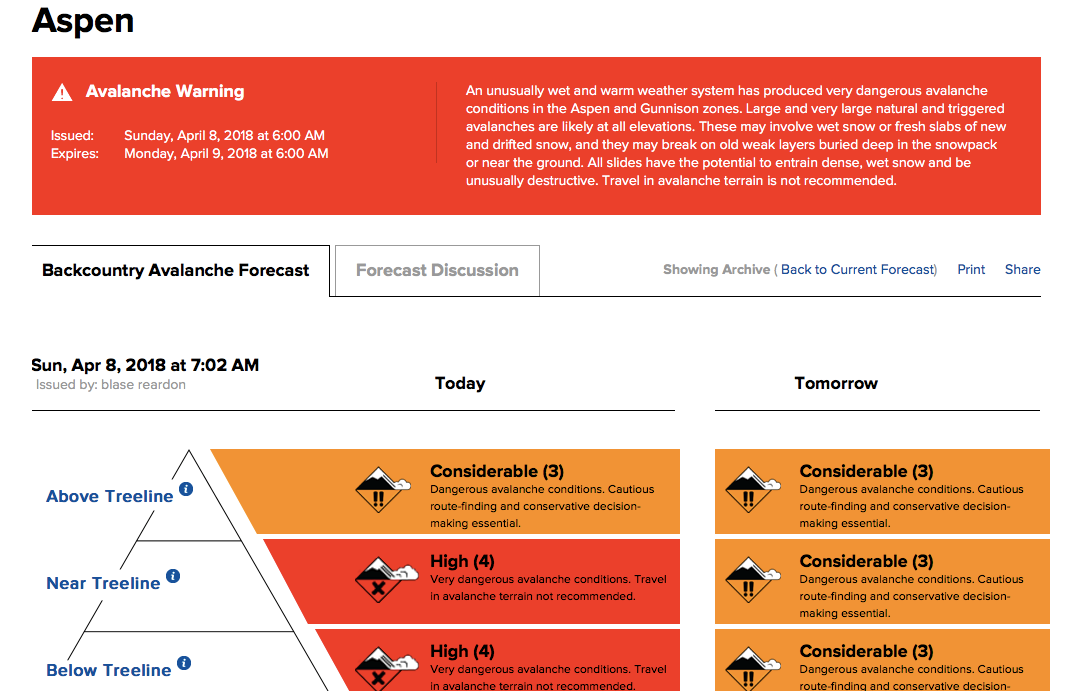

CAIC forecasters issued a High (Level 4) avalanche danger the morning of the accident (Figure 3) and an accompanying Avalanche Warning advising people to stay out of avalanche terrain.

Post-incident interviews revealed that the two skiers involved discussed the unusual storm. The survivor stated that he did not read the avalanche forecast that morning. We don’t know if the victim knew that there was an avalanche warning in effect or if he was aware of the current backcountry avalanche forecast.

FIG. 3: TRIGGERED SLIDES IN MAROON BOWL, 4-8-18. THE GREEN ARROW MARKS A SMALL AVALANCHE TRIGGERED BY AHSP WITH AN EXPLOSIVE CHARGE ON THE MORNING OF APRIL 8. THE BLUE ARROWS MARK LARGER AVALANCHES TRIGGERED BY THIS SMALL ONE. THESE AVALANCHES WERE VISIBLE BEFORE THE TWO SKIERS DESCENDED THE TREES IN THE LEFT OF THE IMAGE. THE YELLOW ARROWS SHOW THE SKIERS’ TRACKS ACROSS AND ALONG THE AVALANCHE DEBRIS. THE GREEN CIRCLE SHOWS THEIR TRANSITION POINT FROM DOWNHILL TO UPHILL MODE. THE RED ARROW MARKS AVALANCHES THAT WERE TRIGGERED BY SKIERS ASCENDING THE SLOPE THAT AFTERNOON, RESULTING IN A FATALITY. (IMAGE COURTESY OF ART BURROWS)

Clues indicating potentially unstable conditions were evident. The skiers observed fresh avalanches before entering the terrain and crossed avalanche debris to get to their intended route. They determined that the fresh avalanches on adjacent slopes were not pertinent, having seen similar avalanches many times on those same slopes in the past. They completed their initial descent without incident. As they skinned up towards their second descent objective, they made an impromptu decision to continue up a slope steeper than 35 degrees with a terrain trap (trees) below them. The survivor stated afterwards that as they climbed, they noted that conditions on that slope felt different than on the slopes travelled up to that point.

As they climbed up for their next run, they triggered a size 2 avalanche. The crown face appeared to be about 40cm deep and 50m wide. The avalanche initiated on a steep, north-facing, near treeline slope and ran up to 150 vertical metres. It swept both skiers down into sparse trees. The victim stopped at a large tree shortly below a rock outcrop. The survivor continued about 60m further, coming to a rest on the snow surface with both skis still attached to his boots.

Despite witnessing the avalanche, professional ski patrollers and search and rescue members made the excruciating decision not to enter the accident site because of exposure and avalanche hazard. They were able to instruct the survivor via radio to self-evacuate down valley and out of harm’s way. The local Sheriff's Office made the decision not to recover the victim that evening or the next day due to lingering avalanche danger.

THE LESSONS

Some of the lessons are too familiar in avalanche accidents, but they do reinforce the basic messaging we promote as avalanche safety professionals:

- The skiers did not discuss the forecast or the warning, and thus did not discuss the advice to stay out of avalanche terrain. How can we improve our outreach to reach all backcountry users?

- They observed fresh avalanche activity on slopes with the same aspect and elevation but did not find this compelling enough to avoid their objective since they had seen those slopes avalanche many times and intended to avoid those particular features.

- They changed their plan on the fly in the field by climbing higher than intended. They traveled safely until they made this change.

A couple lessons are particular to this storm event, and are cautionary for all of us who work and play in avalanche terrain:

- Terrain familiarity can make it difficult to recognize when conditions are different from those previously experienced. This group had used this route before in a variety of conditions. Weather and climate are changing, and we need to be humble in accepting that our methods and evaluations need to be reconsidered. The tried and true approach to risk management can fail.

- Although we could not readily access the crown in our investigation due to lingering hazard, rain at the front end of the storm was likely a contributing factor. We all need to carefully consider rain on snow effects, even those of us who work in historically cold interior climates.

The intent in writing up this case study is not to cast judgment on those involved. Rather, the hope is that an honest reflection will challenge us all to consider what we can do better and to be on guard for storm systems that fall outside past experiences. The times, they are a changin’.